Last Updated on June 10, 2024

By Ellen Albanese

“How hot do you think it gets?” I asked my husband.

We were watching the billowing clouds of steam swirling around our private spa pool in New Zealand’s Waikite Valley on the country’s Thermal Explorer Highway. An attendant had just shown us how to control the temperature of the silky water cascading down a three-level fountain. The hot, she said, came directly from underground springs at a steady rate; we could adjust the flow of mechanically cooled water. I turned the cold tap off. Within seconds, we had an inkling of how lobsters must feel when plunged into a pot of boiling water.

The spa was our last stop on a tour of geysers, hot springs, and bubbling mud pools along New Zealand’s Thermal Explorer Highway.

We had seen fantastic landscapes in psychedelic colors and heard the primordial burp of boiling mud. And witnessed the incredible power of super-heated water erupting from deep within the earth. We also visited a village where native Maori still use that power to heat their homes and cook their food.

A 300-Mile Highway for Thermal Explorers

The 300-mile Thermal Explorer highway covers much of the upper North Island of New Zealand, stretching from Auckland through the central plateau and Taupo to Napier on the east coast. Well-maintained and lined with neon-yellow Scotch broom bushes, it passes some of the most stunning scenery in the country. In November, New Zealand’s spring, we shared it with logging trucks and an occasional tour bus.

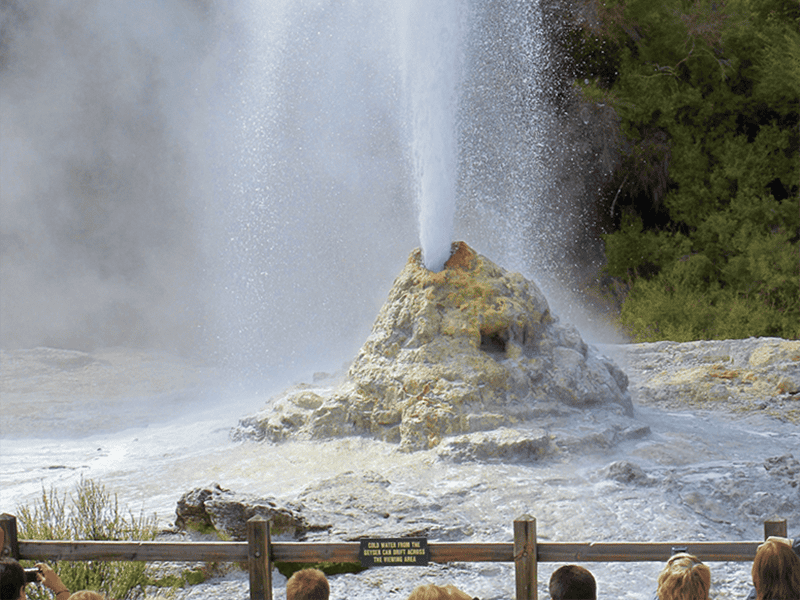

The area’s biggest draw is the Pohutu Geyser on the Te Puia New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute grounds.

Said to be the largest natural geyser in the Southern Hemisphere, it erupts 15 or more times a day. The eruptions are also visible from the neighboring Whakarewarewa Living Maori Village.

Te Whakarewarewa Thermal Valley

The area, Te Whakarewarewa Thermal Valley, was one site until 1997, when a disagreement arose over managing tourism. Te Puia became a tourist site and cultural center, while Whakarewarewa chose to remain a functioning community and operate tours. Some 20 families live there today.

A Whakarewarewa villager we spoke with conceded that residents sacrifice some privacy as tourists come through. “We do a lot of socializing at night,” she said, laughing.

Though she moved away from the village for a while, she said, she always felt its pull. She missed the beautiful ancestral house, or whare tupuna, where important village ceremonies are held and communal cooking and bathing.

The village is wreathed in clouds of steam. Here, as in many sites along the Thermal Explorer Highway, you learn to be patient when trying to see a building, a spring, or a cave, waiting for the vapor to clear for just a moment. It’s a precarious existence; we saw at least one wooden house that had succumbed to heat and moisture and fallen in on itself. While scalding waters are now fenced off, we can only imagine the dangers children faced in an earlier time.

Communal Steam-Box Ovens

Cooking is done in communal steam-box ovens, our guide said. The wooden cases are built where vents concentrate steam from underground springs that average 320 degrees. The hottest spring in the village rises above 500 degrees.

Villagers pack vegetables, meat, or fish in muslin cloth tied with a rope, then drop them into the steam box. Leafy vegetables cook in three minutes. For lunch, we had a hangi, or steam-cooked meal, of chicken, corned beef, potato, sweet potato, carrots, bread stuffing, cabbage, and corn on the cob — not unlike a traditional corned beef and cabbage dinner.

Our guide said villagers don’t need soap or shampoo in the communal bathing area because the water is so soft. Almost oily to the touch, its therapeutic properties – relieving pain and promoting sleep – are the stuff of legend along the Thermal Explorer Highway.

Cultural performances include traditional chants and songs, dances using swinging poi balls for percussion, and stick games. Many men’s dances are performed in the traditional aggressive “war stance,” involving fierce expressions, grimaces, protruding tongues, and bulging eyes.

Viewing the Geysers

The tour wrapped up with a view of the geysers. Pohutu, reaching heights of 100 feet, often erupts simultaneously with the Prince of Wales Feathers geyser, a few yards away. From an observation platform at Whakarewarewa, we watched the water and steam swirl and felt the spray on our faces. To our surprise, the eruptions continued for 15 or 20 minutes, jetting water blending with puffy, low clouds to create a roiling, surrealistic canvas of white.

For sheer spectacle, it would be hard to top Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Wonderland.

The Lady Knox Geyser erupts daily at 10:15 a.m., activated by a soap deposit. (The area was once part of a prison camp, and it is said that the prisoners discovered the geyser’s action while washing their clothes.) The geyser is just the beginning of a fascinating journey on the Thermal Explorer Highway.

Sacred Waters

Wai-O-Tapu (sacred waters) covers some 7 square miles, with the volcanic dome of Maungakakaramea (Rainbow Mountain) at its northern boundary. The area is covered with craters, cold and boiling mud pools, water, and fumaroles, vents where steam escapes from underground. The gray, rocky landscape, with little vegetation, looks like the moon’s craters, it all making the vivid colors of the mineral-dyed pools even more breathtaking.

A boardwalk stretches over the Champagne Pool, with its distinctive reddish-orange petrified edge ringed by steaming, bottle-green water. It’s a constantly changing panorama, as steam lifts briefly to reveal one otherworldly color, then another. The largest spring in the Wai-O-Tapu district is 200 feet in diameter and nearly 200 feet deep, with a surface temperature of 165 degrees. Its bubbles are due to carbon dioxide, and its overflowing water creates the Artist’s Palette, a series of colorful pools. The water in Devil’s Bath, a large crater near the park entrance, is the color of a neon green highlighter.

Mud Pools

It’s a short drive along the Thermal Explorer Highway to Wai-O-Tapu’s Mud Pool, which is said to be the largest in New Zealand. If it had rained recently, as when we visited, the mud pools would have been less viscous; the rainwater would have tended to sit on the top. But even a rain-soaked mud pool is an impressive visual and auditory experience — wonderfully swirling, glossy, boiling, concentric circles accompanied by a guttural burping sound. Since each little pool shimmies and vibrates until the heat below causes it to explode, the trick is to stare at one spot until it erupts; otherwise, you’re always just missing the action.

Having seen and learned about New Zealand’s thermal wonders, we were also eager to immerse ourselves in the legendary waters. Just 4 miles from Wai-O-Tapu, Waikite Valley Hot Pools range from 81 degrees to 106 degrees F. The site includes six large public pools, smaller mineral pools, hot tubs, and private pools that allow users to control the temperature. Every pool is also filled daily with fresh geothermal water from the Te Manaroa boiling spring. It’s the largest single source of 100 percent pure boiling water in New Zealand.

As clouds of steam drifted by our private, open-air spa, we sank into the soft, calcite-rich water. While it didn’t take away all our aches and pains, it was silky, relaxing, and plenty hot.

Leave a Reply